By Michael Mozdy

|

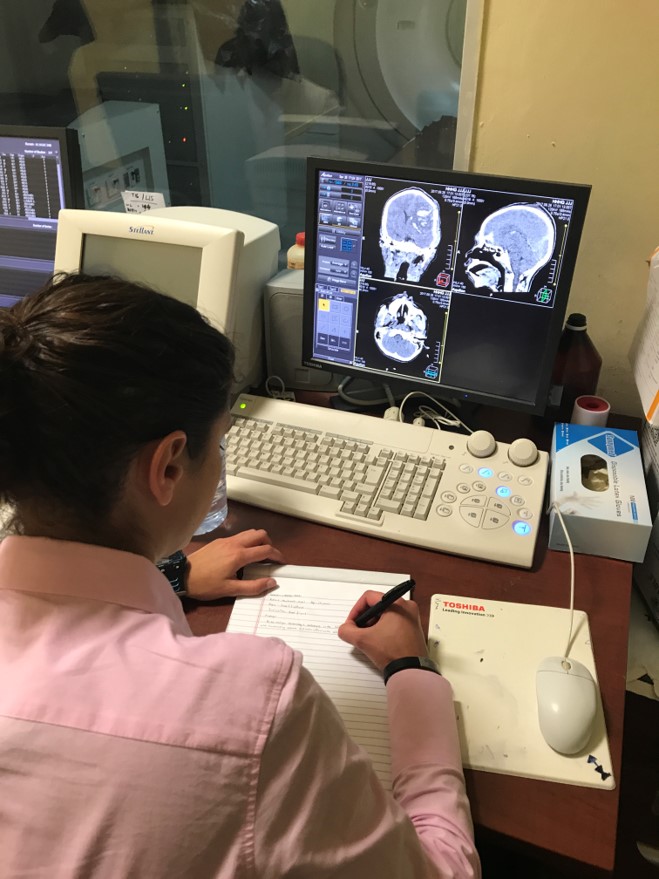

| Bryn Putbrese, MD, working in Ghana during her global imaging outreach 4th year residency experience. |

Radiology residents face a whirlwind four years learning how to interpret studies in all of the body systems, from neuroradiology to musculoskeletal imaging (and much more). Before they head off to their fellowship year where they sub-specialize in a particular area, we present them with an opportunity to learn in a very different context – in a developing foreign country where they transition from student to teacher and encounter a drastically different health care system.

Fourth year radiology residents in our department have the opportunity to create a global imaging outreach experience as one of their electives. “We are committed to resident participation in global outreach,” says residency co-director Leif Jensen, MD. “We would like to see one resident a year have this kind of experience, but there is room for more to participate if they are interested,” he adds.

In 2016, Scott Parker, MD traveled to Uganda where he taught at a conference and provided hands-on clinical expertise at a large hospital. Similarly, in 2017, Bryn Putbrese, MD spent a month in Ghana where she taught medical students and interpreted all manner of clinical radiology studies.

Both physicians have continued professional relationships with colleagues in these African nations, and both see the experience as one of the most formative and impactful in their entire residency. Their stories are a good reminder that the world’s population, especially in developing nations, can greatly benefit from the surfeit of resources and expertise we have in our medical professionals.

Care in Kampala

Uganda is the size of Utah, but with 40 million people in its borders while we have just 3 million. It’s like packing the entire population of California into Utah. It’s also in the bottom 25 poorest countries in the world, with 80% of adults existing on less than 1 dollar a day and 50% of the population under the age of 15.

|

| City of Kampala. Photo: Wikimedia. |

Uganda’s nationalized health care system pays its physicians poorly and the equipment suffers from age and lack of maintenance. Private health care clinics dot the cities, where physicians can make better money thanks to wealthier people paying up front for their exams and treatments. Thus a struggling system for the majority of poor citizens exists side-by-side with one for those who have money.

|

| Scott Parker, MD, performing ultrasound in Uganda. |

Even at the government-run hospitals, patients have to pay up front for common outpatient services like an ultrasound. So people wait until they’re very sick to go to the doctor because they want to make sure they really need to spend the money it takes to get a diagnosis.

As a result, Parker saw advanced cases he never encounters in the U.S.A. During his two-week trip, he first presented four talks at a conference for Ugandan radiologists and residents. Next, he visited some schools and churches in order to lay the groundwork for an education research project he’s conducting to more effectively deliver breast cancer screening education to young women. Finally, Parker spent several days doing hands-on clinical work with African colleagues. He witnessed firsthand the difficulties the health system presents.

"Despite the fact that treatment for breast cancer is provided free of cost at the Uganda Cancer Institute, up to 89 percent of new breast cancer diagnoses present with stage III or IV disease," he reports. "The average woman waits over two years after self-detecting a lump before seeking medical care." The treatment that is free and available is at that point not that helpful.

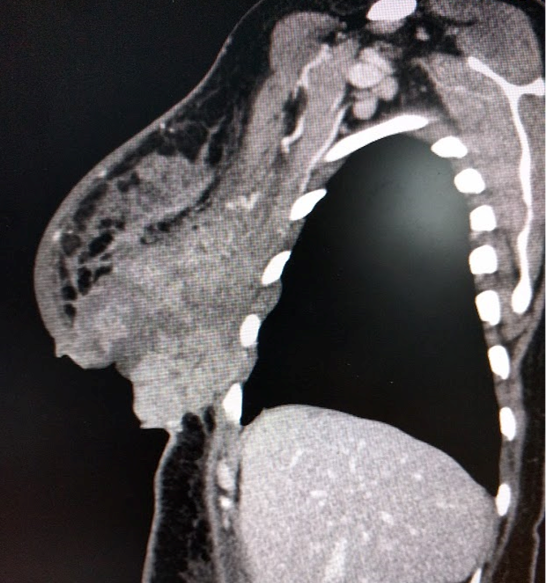

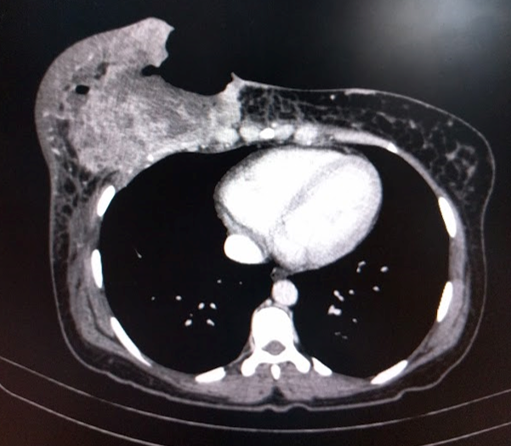

Parker saw some advanced pathology in this short time, and not just in mammography.

|

| Side view (left) showing advanced cancerous breast mass and top view (right) showing how the tumor has progressed so far that it has actually connected with the exterior skin of the patient. |

|

| Scott Parker, MD, lecturing at a radiology conference in Uganda. |

The availability of imaging technology is another vast gulf. Parker heard that there were two MRI machines in Kampala, a city of 12 million, although he didn’t encounter one. Contrast that with 13 MRI machines in University of Utah Health alone.

Returning to the U.S. was a mixed blessing – on one hand physicians can feel like they’re making a difference in the life of a patient with the technology and timing that is effective. On the other, “it makes me ponder why life and medical care is so unequal” Parker admits. “It makes me feel like I need to continue to be generous with humanitarian efforts.”

A Guest in Ghana

|

| Photos taken by Bryn Putbrese during her imaging outreach trip to Ghana. |

In summer 2017, Putbrese spent a longer time – 1 month – in Ghana. Also roughly the size of Utah, with a population of 28 million, Ghana faces many of the same challenges as Uganda: a very poor population, a government-run hospital system shadowed by a secondary private care system for those with means, and a poverty-driven phenomenon of patients coming to the hospital too late in their disease progression.

Putbrese spent the bulk of her time at an imaging center in the district capital of northern Ghana, Tamale, where she taught medical students and interpreted clinical scans with her African colleagues. The imaging center housed ultrasound, x-ray, mammography, CT, and even an MRI machine, although the helium-based MRI had run out of helium, which would cost $90,000 to replace, so it was indefinitely out of commission. What’s more, the center only performed 5-10 CTs a day because so few people could afford one.

Putbrese was disheartened at some of what she witnessed as a result of the lack of resources in the area. “I saw a 14-year-old child with head trauma needing a neurosurgeon but nobody comes and they die,” she relates. “There were literally dead bodies hanging out in the ER for days.”

|

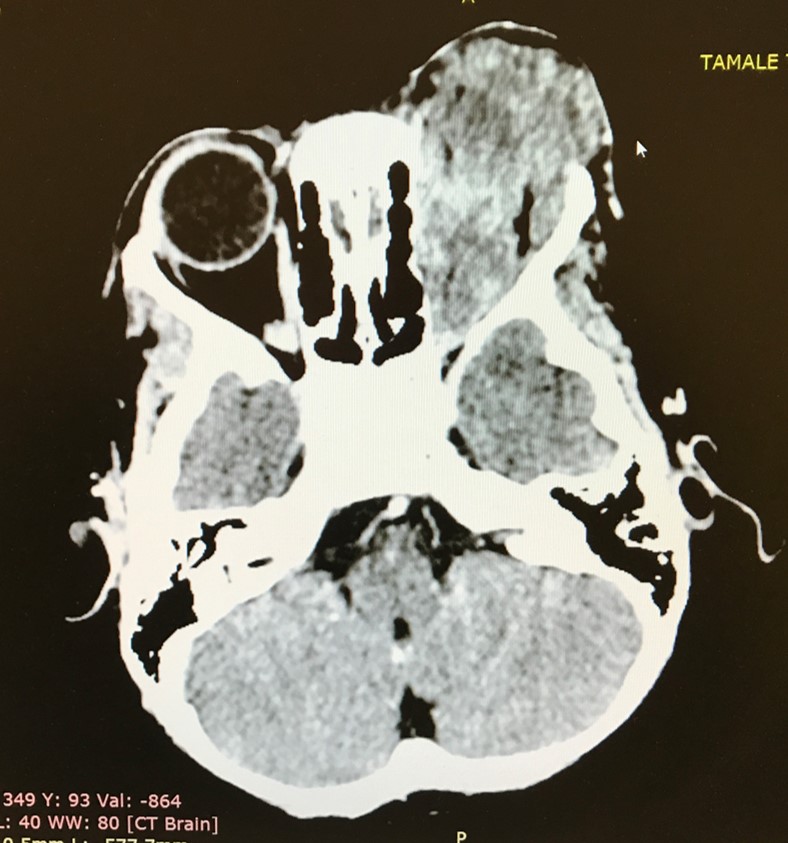

| Example of a retinoblastoma (tumor of the eye) seen by Putbrese while in Ghana. |

Through these sometimes appalling conditions, Putbrese encountered physicians and medical students eager to learn and to improve the quality of medical care in the country. Physicians in Ghana enter into a 6-year medical school directly out of high school, followed by 4-5 years as a house officer and medical officer, and then finally 3 years in a residency. She was able to provide lectures and hands-on tutorials for a class of 118 fifth-year medical students. She notes that no matter what specialty a physician ends up with, a good knowledge of what radiologic scans are capable of will help him or her better care for patients.

|

| Some of the medical students taught by Putbrese in Ghana. |

Plagued by the systemic problems she encountered in Ghana – much like those in Uganda – Putbrese reflects on the existential crisis that many medical aid workers encounter. “Once you are on-site,” she explains, “you realize that you are only a very small piece of the puzzle. What is the point of making a diagnosis when the disease is untreatable or the needed resources are unavailable? You have to overcome these internal struggles and do what you can with the available resources.”

For her part, Putbrese is writing grants to get a digital mammography unit and portable sonography for breast ultrasound to the Tamale hospital. She is also trying to get one of their radiologists to come here and train in interventional radiology procedures. She admits that a system-wide change to patient access and affordability is desperately needed, but, she says, “I came to realize that one person can make a difference; it may be on a very small scale, but over time small changes can lead to big improvements.”

|

| Bryn Putbrese, MD (second from right) with colleagues in Ghana. |

An Opportunity for Those Motivated

The global imaging outreach program is supported by the department, but make no mistake, it demands a motivated individual who wants to craft his or her own experience. Both Parker and Putbrese spent months investigating opportunities in various countries and making contacts with physicians who had an established collaboration or practice in these countries. They made their own arrangements for travel, lodging, and the range of experiences they were to have. The School of Medicine’s Global Health Education Program is a great source of contacts and tips for residents considering this 4th year opportunity.

Jensen recognizes the work and grit it takes to complete this global imaging outreach. He believes it speaks to the excellence of both individual physicians and the residency program. “We are proud that the skills and knowledge our trainees gain in residency allow them to have an impact in resource-poor settings, assisting in direct patient care and providing radiology education,” he says.

It’s certainly an experience both Parker and Putbrese rank highly in their professional lives. “Hands-down this was the most rewarding experience of my entire residency,” declares Parker. “People appreciated me so much – I learned a lot from being there and felt like I was doing some good.”

Putbrese has a new-found appreciation for the resources available here. “I am very grateful for the opportunity to have worked in Ghana,” she says. “Working in a third world country certainly puts things into perspective as to how lucky we are in the United States to have easy access to good medical care.”