By William Morris

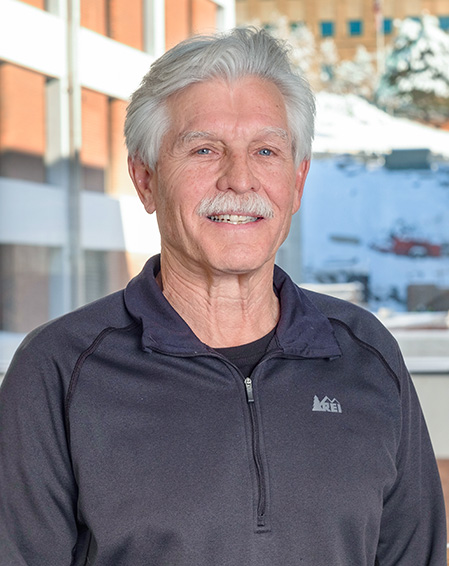

Since the start of his career with the University of Utah 41 years ago, H. Ric Harnsberger has become one of the most recognized experts in the field of head and neck radiology. He has published a prolific 11 books and over 200 articles in this area, including the field’s best-selling textbook: Diagnostic Imaging: Head and Neck, published in 2004. Harnsberger has held esteemed positions such as the 2007 President of the American Society of Head and Neck Radiology (ASHNR) and the R.C. Willey Chair of Radiology at the University of Utah.

Hugh Fredric (Ric) Harnsberger grew up in the quiet hills of suburban Marin County, just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, in what is now a wealthy Silicon Valley bedroom community. In his youth, the area was a bucolic rural setting, ideal for an adventurous childhood. “You could hike all day—I did—and sometimes not see another person,” Harnsberger remembers. “Maybe a cow.”

From an early age, Harnsberger knew he wanted to be a doctor. His parents, working at University of California Berkeley, both held PhDs in Chemistry. They may have provided an early model for an academic career, but Harnsberger’s true inspiration came from an uncle. His father’s brother worked as a rural general practitioner, serving a small town near Mt. Shasta.

|

“We would visit his house on vacations,” Harnsberger recalls, “just goofing around. People would come to the door with these injuries.” Seeing how his uncle’s medical practice affected the community gave Harnsberger an early idea of what he could do with his life.

“He was this larger than life figure for me as a boy,” he recalls. “I vividly remember standing next to him, and some guy came to the door with this huge hook going through his hand from a fishing accident.” Harnsberger clutches his own hand for emphasis, as though reliving the drama. “My uncle just clipped it off, pulled it out, and dressed the wound.”

A Near-Death Experience

Harnsberger studied zoology at UC Davis, and later attended medical school at UCLA.

It was in 1976, during his third year as a medical student at UCLA, that everything changed. An otherwise healthy person, he suddenly fell seriously ill. “I remember waking up with crashing headaches,” he says. “I thought it was a bad flu.” The clinicians at the student health clinic thought so too; they prescribed antibiotics and sent him home. Three days later, he woke up with expressive aphasia—he couldn’t speak.

In the emergency room, the doctor looked Harnsberger in the eye and asked: “OK, what drug did you take?”

“Of course, I couldn’t answer him,” Harnsberger says, laughing about it now. “So, the doctor handed me a pen and told me to write it down. The pen just wandered across the page. I couldn’t speak or write, and that’s when he looked for signs of brain swelling.”

All of this stemmed from a sinus infection, which caused a subdural empyema, or the spread of pus along the brain. This empyema led to osteomyelitis in the bone of Harnsberger’s skull. Fortunately, his doctors were able to detect this empyema with newly developing CT technology.

“They had to remove the anterior plate of my frontal sinus because it was just mush,” he says, gesturing to a long indentation on his forehead, just between his eyes. Though the infection destroyed some of Harnsberger’s bone and required surgery, he considers himself lucky. This type of severe infection often left patients with lasting disabilities. For some, it resulted in death.

“The surgeons saved my life,” Harnsberger emphasizes. Thanks to new technology in neuroradiology, surgeons were able to see the affected areas within the skull, make a swift diagnosis, and operate before the infection became fatal.

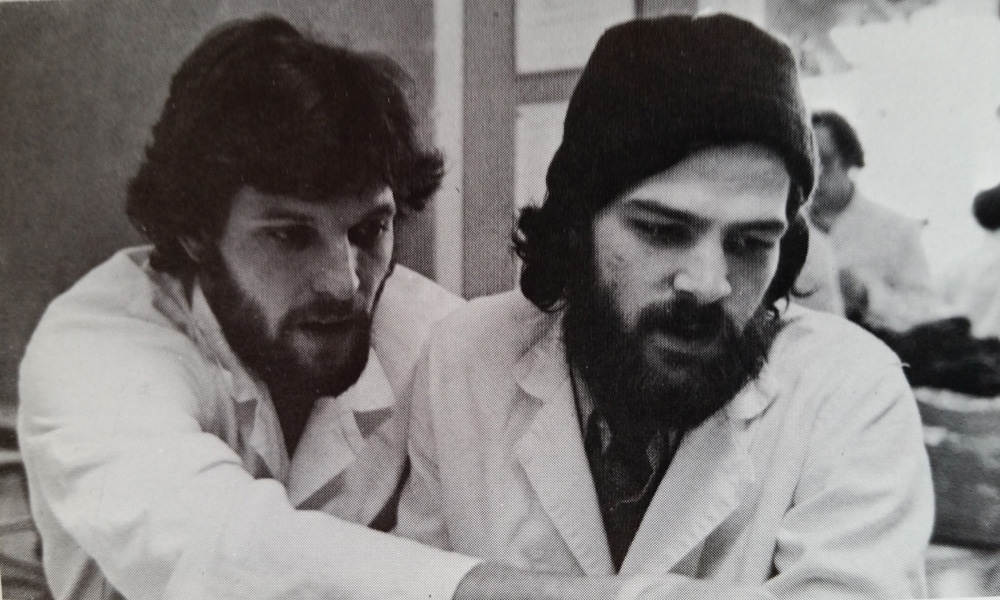

Ric Harnsberger (left) and Randy Moeller in the Anatomy lab at UCLA in the mid-1970s.

At the time, Harnsberger was studying internal medicine. He was spending long days in the hospital clinical service, witnessing the effects of disease on seriously ill patients. “I think I was depressed,” Harnsberger admits. This was in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, and patients with the most severe cases came to UCLA for treatment. “There were young men coming in and dying from pneumocystis and other diseases all the time.” This constant, direct exposure to illness and death affected Harnsberger’s perspective on medicine. He was discouraged and depressed, and suspects that his mental and emotional state may have had some bearing on the severity of his sinus infection. “I was thinking about leaving medicine,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘I’m going to die. This is going to kill me.’”

As he was finishing medical school and recovering from his near-death experience, Harnsberger searched other fields for a career that would match his particular interests.

From Newbie to Expert

But Harnsberger realized he could still practice medicine and positively affect a community without becoming a general practitioner. His own life, after all, had been saved by radiologists and neurosurgeons. His illness was a momentary setback, but did not stop him from graduating on time and seeing a new future for himself as a physician.

So, 41 years ago, Harnsberger came to the University of Utah as a resident in the Department of Radiology. “The University,” he says, “had just recently created a new focus on head and neck radiology. It was a field that was in its infancy.” By Harnsberger’s estimation, there were roughly 200 people in the world doing head and neck radiology when he began his career in the field.

Surgeons operating on the head and neck needed someone to interpret scans, and Harnsberger—a fellow at the time—had the interest to try. The Chief of Neuroradiology knew that Harnsberger was interested, and approached him with a job offer.

From then on, the Head & Neck Surgery Department sent all of their imaging studies straight to Harnsberger. He considers himself very lucky to have been part of the group of physicians who played an important role in creating a new field of radiology.

|

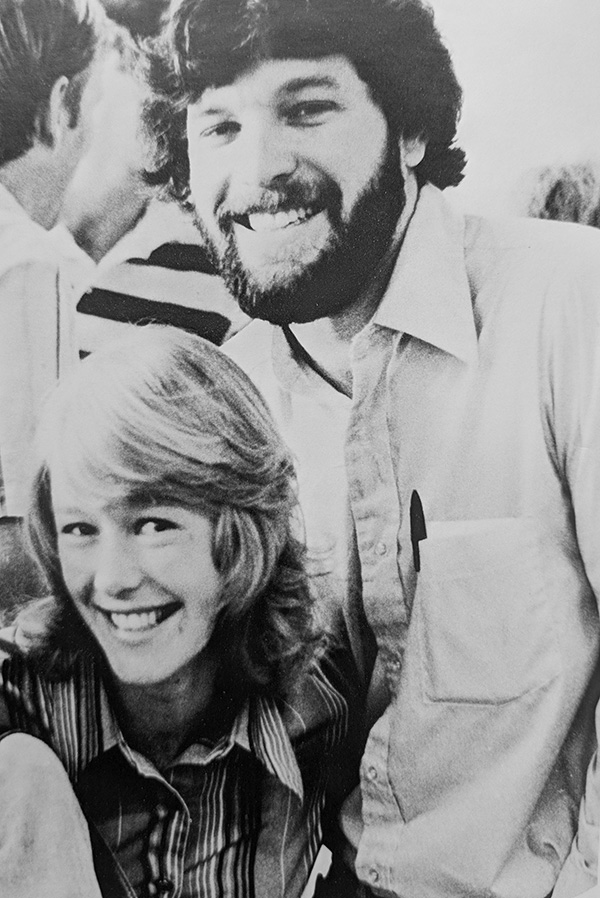

| Ric and future wife Janet, senior year at UCLA Medical School. |

Since that day, Harnsberger has been a major force in Head and Neck Radiology. In addition to his rich record of publishing peer-reviewed articles and his professional titles, he has received numerous awards, including the Roentgen Centennial Award from the Radiological Society of North America, the ASHNR Gold Medal, and the University of Utah’s 2013 Distinguished Innovation and Impact Award. He spent his career doing everything he could possibly do: “You can teach, you can do research, you can administrate, and you can do high-end clinical work,” he recounts. “What fun to have so many different challenges during a person’s career.”

In a largely unexplored field 500 miles from the next academic medical center, it was necessary for Harnsberger to make his career up as he moved along. “The University Medical Center was a great place to be,” he says, “because there were a million unanswered questions.”

Harnsberger is modest about his career, acknowledging that a new field is ripe for discoveries. He pursued research and clinical cases during long days, and spent his nights writing papers. If he made a mistake and didn’t understand why, he started a study to figure out what that error meant, because other physicians needed to know.

“I was constantly busy,” he admits. “My wife Janet was a busy Pediatric Gastroenterologist too, so for 25—maybe 30—years, we got up early and went to bed late. Our lives were full, with everything, including family.” The Harnsberger family included sons David, Dan, and Dylan, each contributing energetically to the chaos. Ric and Janet embraced the chaos, traveling with their family circus, skiing together and coaching soccer.

A Late Stage Career in the Wild, Wild West

In recent years, Harnsberger has reduced his work load to half-time. This change started in the early days of creating his company, Amirsys, as a way of committing time to a new enterprise without leaving the University. He wanted to develop software that could support radiologists worldwide in making accurate diagnoses.

“The University of Utah allows people to grow and explore their careers in a unique and positive way,” Harnsberger asserts, reflecting on how the Chair of Radiology, Steve Stevens, created a half-time position for him given his new career goals. “Nobody ever told me, ‘you can’t do that,’” he says. “They encouraged me to do what I was trying to do. People here will help you find a way to grow your career in all kinds of directions.”

This level of freedom is something Harnsberger sees as unique and paramount to the University’s environment. Thinking about the opportunities he has had to explore a field so full of uncertainty and unanswered questions, Harnsberger concludes: “The University of Utah is still the Wild, Wild West.”

Now, Harnsberger teaches in the morning, does clinical work a day or two a week and spends the rest of his time traveling with his wife, spending time with his son and grandson and growing blackberries in his back yard.

Ric and family. Back row left to right Dan, Dave, Ric. Sitting left to right Dylan, Janet and grandson Roen.

Ric and family. Back row left to right Dan, Dave, Ric. Sitting left to right Dylan, Janet and grandson Roen.

“When I’m finally retired,” Harnsberger reflects, “it will be sad, but also a time to celebrate the community that I’ve been a part of.” He has established connections at the University—long-lasting bonds that span an entire career—and he knows those connections won’t soon sever, even after retirement. “They’re called friends.”