By Michael Mozdy

A lot of people may not know this, but our hospitals were full even before the pandemic. About two years ago we added a floor of beds at University Hospital and within 3 months they were full, too. “It’s understandable – our care is awesome!” declares Sam Finlayson, MD, MHA, MBA. Formerly the Chair of the Department of Surgery, Finlayson has recently been appointed the Associate Vice President for Clinical Affairs and the Chief Clinical Officer for University of Utah Health. He is very interested in where we go as a system now that our hospitals are chock full.

“Our most important asset is the exceptional expertise of our physicians and staff,” states Finlayson. “This has created great demand for our health services.” Finlayson’s job is to help plan where University of Utah Health goes in the next decade and he is focused on ways to get our expertise to anyone who wants it – without building new hospitals.

Partnerships and Pipelines

Part of Finlayson’s puzzle is that many beds in our hospital are occupied by patients who are recovering from routine procedures or other conditions that may not require the sophisticated (and expensive) resources available at University Hospital. The solution is to care for these patients in other local and regional hospitals while getting the sickest patients and those most in need of advanced care to University Hospital. “We’re starting to do this in places like Mountain West Hospital in Tooele,” says Finlayson. “Our docs, their hospitals – we’re providing them with high quality care and access for their patients who need to be at University Hospital.” The upshot is that we can provide University of Utah level-of-care without taking up beds at University Hospital. Partnerships like this help us ensure that the right people are in our hospital while we maintain an excellent level of care in other settings.

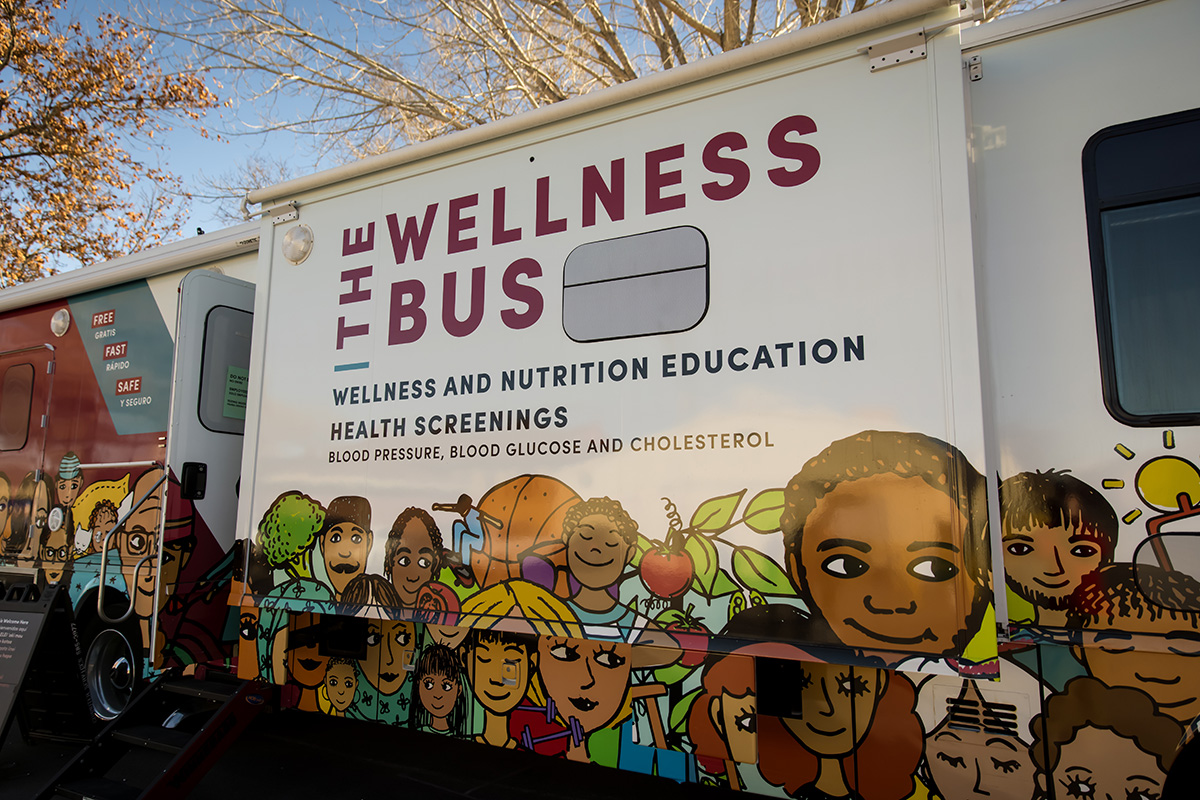

This is just one example of the type of more efficient and effective health care delivery model Finlayson likes. Other activities in motion include a robust telemedicine system to help those in rural Utah and mobile outreach like our Wellness Bus and the Cancer Screening and Education Bus. These tactics help us bring our world-class expertise to more and more people without having to invest in expensive bricks-and-mortar projects like new hospitals.

Diagnostic radiology can empower the model of care delivery that Dr. Finlayson envisions. Our radiologists can provide expert-level interpretations of scans, even remotely. Certainly, every patient wants the best, most expert interpretation of their MRI, CT or, PET scan. If we start providing interpretations for partners and other hospitals in the region, however, it becomes a critical strategy how large of a physician force we need to have in the Radiology Department. “Our department is growing steadily, or I should probably say, rather quickly,” says Satoshi Minoshima, MD, PhD, the Anne G. Osborn Chair of Radiology and Imaging Sciences. “It is of utmost importance to maintain the highest level of quality in our subspecialized radiology services while facilitating faculty engagement, academic endeavors, and their wellness.”

Minoshima has invested in physician leadership to help with this very concern by hiring a Vice Chair for Wellness and Engagement, Sharon Kwan, MD, MS. It is no secret that burnout is an issue in academic medical centers where the sickest of the sick come for their treatment, and radiologists in particular struggle with endless workloads over which they have little control. A good work-life balance is something Minoshima and Kwan are determined to support.

Being Cost-Conscious in a Cost-Woke World

Over the past few decades, a national spotlight has illuminated the incredibly high costs in U.S. health care. Apart from the astronomical dollar values being spent by systems, insurance providers and patients alike, much research in this area points to the mis-alignment of incentives among the different groups. Hospitals are incentivized to keep every bed full at all times so they can recoup the costs of running the facility and equipment. Physicians are incentivized to do as many procedures and interventions as possible because their compensation is tied to the volume of interventions they do. Insurance providers are incentivized to keep people out of hospitals and physician rooms because they get to keep more of the insurance premiums they collect instead of having to pay out for interventions. And patients are caught in the middle – incentivized by the need to stay healthy, but also to save money. Any discussion of health care in the future has to deal with the problem of differing incentives.

|

| Sam Finlayson, MD, MHA, MBA |

Finlayson is particularly interested in seeing what can be done about re-aligning physician incentives. In his experience, tying physician compensation to the volume of interventions done is not in the patient’s best interest nor the physician’s interest. “Fee-for-service burns people out,” he states unequivocally. Like Minoshima and Kwan, Finlayson wants to maintain a good work environment. He also notes that when physicians simply look at their work as a game of racking up the most procedures, they take the human patient out of the whole equation. “Dehumanization hurts culture,” he says, “and bad culture is bad for patient safety. It’s a bad spiral.”

The first lesson he shares is that a salary alternative might not be so bad. “In surgery,” Finlayson asserts, “there doesn’t seem to be a big difference in compensation between salaries and fee-for-service model.” He acknowledges that volume will still be a driver for some physicians, however, especially those who provide very specific procedures. One tactic he suggests is to compensate something other than the costly surgery or procedure, for instance, tying compensation to consultations rather than surgeries. The incentive in this model is more closely aligned with a patient’s interests, which is knowing about their condition and their options rather than just getting an intervention done.

Radiologists, too, receive a large part of their compensation from insurance payments for each study that they interpret. On one hand, Finlayson wonders if radiologists’ incentives could be tied to something else, but at the same time he acknowledges the incredible value of radiology in modern medicine. “It’s easy to think that radiology is very expensive,” he says, “but it’s not about high cost, it’s about high value. Services that provide earlier and more accurate diagnoses are extremely valuable.” To illustrate his point, if a cancer is detected earlier, the costs to treat that patient over 10 years can be a fraction of what they are if the cancer isn’t detected and becomes much more invasive in the body. What’s more, aligning patient incentives and physician incentives isn’t as problematic in radiology because every patient and provider wants the same thing: a timely, accurate interpretation of a study. Doing more interpretations isn’t counter to the value of health care for patients – it just enables more patients to receive important information about their conditions. Plus, since other physicians are the ones ordering the tests, radiologists have limited impact on problems like over-ordering expensive studies. Even better, the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences is recognized by the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services as a Provider-led Entity (PLE), thanks to Drs. Yoshimi Anzai and Edward Clark’s efforts, in which multi-disciplinary leaders at University of Utah Health can develop our own appropriate use criteria (AUC) for imaging services to best support the highest value of patient care and mitigate overuse.

Finding a Place for Population Health

Another area where University of Utah Health is lining up incentives is the population health model. Since we are an insurance provider as well as a health care provider, we are doing a targeted trial with a specific population of patients. These patients have complex medical problems and a history of visiting our hospitals and various outpatient clinics several times a month throughout the year. This is very expensive for an insurance company to cover, it’s inconvenient for the patients whose care seems disjointed, and it’s very inefficient for a health care system. So, we’ve set up an intensive outpatient clinic to provide all of the services these patients might need. While it was expensive to set it up initially, the overall cost of care for these patients went down. We continue to tailor services for this complex population to keep them healthier, and it makes sense for everyone involved.

There are about 15-20% of our patients for whom we are “on the hook” financially – when they use less services, we do better. Other systems in our area have upwards of 40% of their patients in this category and we have seen many local wellness PR campaigns as a result, encouraging overall health and regular primary care visits so that patients are less likely to develop expensive health issues.

As Finlayson looks to the future, there are many strategies that he is excited about. In the end, though, he is proud that we are an academic health system where research drives new medical innovations, where health care providers of the future learn from our experts, and where clinical sub-specialists have a home to provide their niche interventions. We will never be a straightforward business, and that’s not our mission. “As a tertiary and quaternary care academic health center, we’ll always be a part of the pay-per-service health business,” Finlayson admits. But that’s not a bad thing across the board. “People from throughout our region seek our specialized services,” he adds, “and we wouldn’t be at the forefront of medicine, attracting the brightest physician minds if we didn’t offer them.”